|

|

|

|

| 5. SUSTAINABLE CONTROL STRATEGIES |

|

5.1 Soil solarization Soil solarization is a simple, cheap, and highly efficient method to control weeds effectively. The only price input is the plastic sheets. To solarize the soil, first the soil must be in moist condition and covered with 0.125-mm thick black polyethylene or 0.1-mm thick transparent polyethylene sheet for 4 to 6 weeks. The sheet should be in a full stretched condition, and the edges buried in the soil to hold the sheet in place. Solar radiation heats the soil under the plastic sheets and the temperature rises to 45-50oC. The heavy heat affects the weed seeds present in the soil under the polyethylene cover. The effectiveness of the soil solarization depends on the exposure time and the prevailing temperature. In addition to weed control, soil solarization controls plant diseases, and it alters some of the physical and chemical properties of the soil to promote better crop yield.

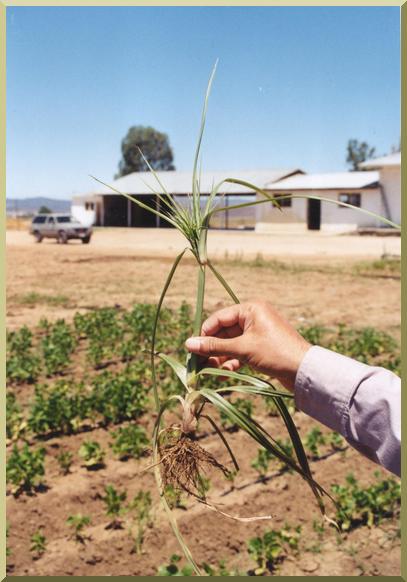

5.2 Tuber marketing Parts of the nutsedge, particularly the tubers of the yellow nutsedge, have been marketed as food for animals and even humans. Other parts of the purple nutsedge may also have economic uses. Additional research will determine whether this is a feasible control strategy for the Ojos Negros and neighboring valleys of Baja California.

5.3 Feed for pigs and wildlife There is evidence that pigs can be used effectively to control coquillo. Pigs will search and eat the tubers, particularly those of the yellow nutsedge. Wildlife such as ducks and turkeys are also fond of the tubers of the yellow nutsedge. Research is needed to determine whether use of the nutsedge as animal feed is a feasible control strategy for the Ojos Negros and neighboring valleys of Baja California. 5.4 Shading The coquillo requires plenty of sunlight and water for its continued growth and development. One strategy for coquillo control that is being used in Ojos Negros is to rotate alfalfa into a coquillo-infested field. Alfalfa effectively shades the ground, inhibiting the coquillo aerial parts from growing. Control is effective while the alfalfa is being cultivated, although there is no experience to indicate that the coquillo will not come back after the field is rotated back to vegetables. 5.5 Experience in Valencia, Spain It is perhaps in Valencia, Spain, that the yellow nutsedge (C. esculentus L.) is best valued for the quality of its tubers. Researchers at the Universidad Politécnica de Valencia (Polytechnic University of Valencia) have studied the economic uses of C. esculentus since 1981. In particular, España and Maroto (1984) have published a book on the agronomy of the chufa (Cyperus esculentus L.). Their findings are reported here.

The chufa crop, although small compared to other popular staples, has increased steadily in Spain. The main reason appears to be the increase in the consumption of horchata, coupled with the increased profits associated with the mechanical collection of the tubers. The majority of the chufa grown in Spain is in Valencia.

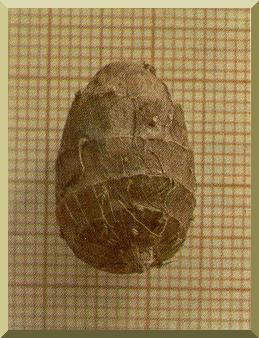

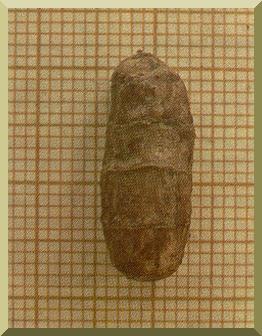

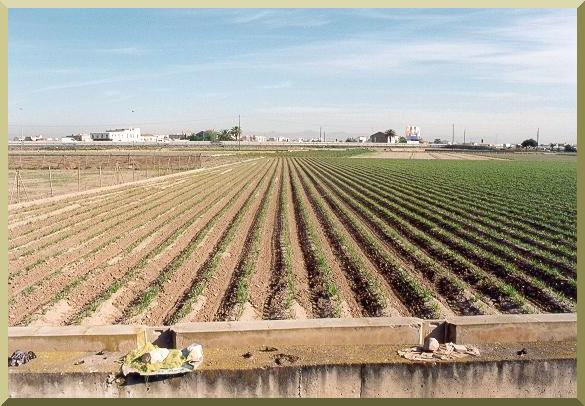

The chufa is grown during the spring, since its aerial parts are very much affected by cold weather. The sprouting of tubers requires a temperature of at least 12oC. The chufa is adapted to sandy and silty-sandy soils; it does not do well in clayey soils. One tuber can produce from 25 to 150 plants (Vaya, 1981). In one instance, one tuber produced 1900 plants and 6900 tubers, all within an area of 2.1 m diameter and 0.23 m depth (Tumbleson and Kommendahl, 1961). The Valencian growers distinguish two types of chufa tubers: "Ametlla," of rounded tubers, and "Largueta," of elongated tubers. Planting is done at the beginning of May, and sometimes as early as April. The number of water applications varies with the local rainfall, from between 10 to 15 per crop. The watering interval is one month during the spring and one week during the summer.

Fertilization studies of chufa has been accomplished with positive results. The Valencian study used two types of liquid fertilizers, and concluded that the chufa responds adequately to target fertilization. Fertilization increased the number and quantity of tubers, and the size of the aerial parts.

"Bedding" is a mechanical or physiological accident which consists of the bending of the aerial parts from nearly vertical to nearly horizontal. Late bedding usually starts in August, when the plants have grown considerably. Prolonged bedding interrupts photosynthesis, and the plants turn brownish in color and start to wilt. Late bedding is normal; however, early bedding, which occurs around July, has the effect of lowering productivity. It appears that agronomic practices that delay bedding, either late or early, have the net effect of increasing tuber productivity. In general, chufa is not fertilized because of the rotation with other crops, among which are potatoes and artichokes, which are fertilized. While there is no rule for chufa fertilization, there is a belief that too much nitrogen could lead to excessive aerial growth and intensify bedding, at the cost of reduced tuber productivity. Nitrogenous fertilizers have shown to reduce the dry weight of tubers, as compared to fertilization with non-nitrogenous fertilizers.

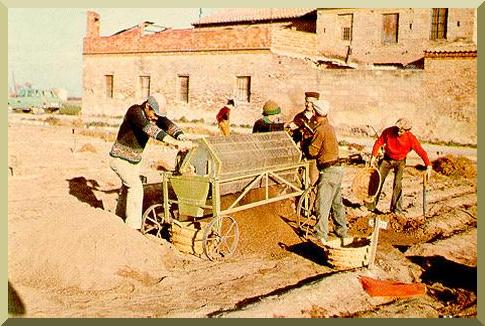

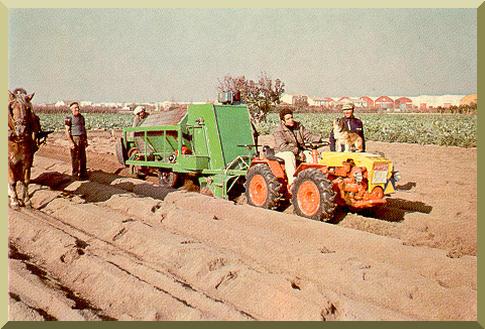

Manual collection consists of a revolving hopper with a screen that separates soil and other impurities, leaving the tubers almost clean, ready for the wash. Mechanical collection is accomplished with a tractor that pulls two bodies; the first body collects the soil, transporting it to a sloping and rotating cylindrical hopper, where the tubers are separated from the soil, and collected at the end of the cylinder.

After collection, the chufas are washed to eliminate rocks, earth, and other impurities. The chufas are bagged and allowed to dry for about 4-6 hours. Production varies between 15 and 18 metric tons per hectare, when the tubers are weighted 4-6 hours after washing, and in rare occasions, it can reach 22 metric tons per hectare. Dry weight is about 60% of the initial weight.

|

|

5.6 References

|

| General | Yellow Nutsedge | Purple Nutsedge | Comparison |

| Strategies for the Ojos Negros Valley | Summary | Coquillo Facts |

| http://ponce.sdsu.edu/three_issues_coquillofacts05.html | 021104 |